China and El Salvador: An Update

El Salvador’s recognition of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in August 2018 was the third such change in Latin America following the end of the informal truce that had restrained the PRC’s diplomatic competition with Taiwan between 2008 and 2016. This pivot also precipitated expressions of concern from Washington, whose reaction to prior changes in diplomatic posture by the Varela government in Panama (June 2017) and the Medina government in the Dominican Republic (May 2018) had been more muted. Since then, El Salvador’s experience with the PRC has been decidedly mixed, reflecting a combination of Central American economies’ short-term limitations in boosting their exports to China, diplomatic pushback and counterincentives from the United States, and the PRC’s failure to follow through on some of its promises—not to mention the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic, which devastated the global economy and put projects on hold across the region.

El Salvador’s recognition of the PRC occurred under the leftist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) government of former guerilla leader Salvador Sánchez Cerén, who had fought against El Salvador’s U.S.-backed junta during the country’s 1979–92 civil war. As part of its initial “thank you” gifts to the Sánchez Cerén government, Beijing sent 3,000 tons of rice and promised $150 million toward 13 infrastructure projects, few of which have been realized yet.

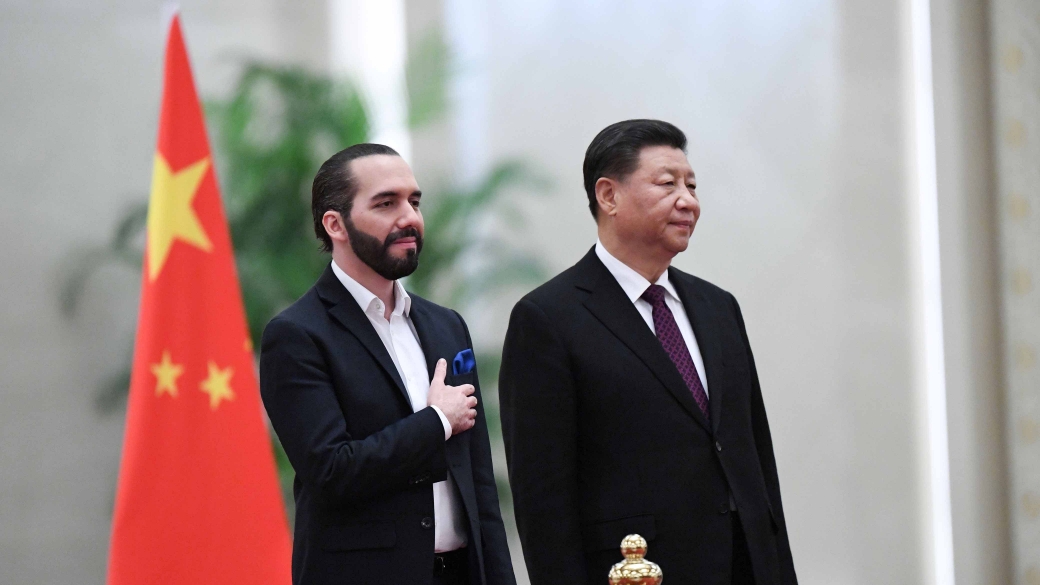

The PRC’s most significant advances in El Salvador occurred under the media-savvy, Washington-friendly centrist government of Sánchez Cerén’s successor, Nayib Bukele. After a very positive visit with U.S. president Donald Trump in August 2019, Bukele proclaimed El Salvador’s friendship and alliance with the United States—but traveled to the PRC just four months later for a state visit with President Xi Jinping. During this visit, Bukele signed a series of MOUs in which China promised El Salvador $500 million in development projects, including a sports stadium and a new $40 million national library in San Salvador, a new tourist pier in La Libertad, $85 million to improve water treatment facilities in La Libertad and Ilopango, and $200 million to support Bukele’s “Surf City” project, which seeks to transform El Salvador’s Pacific coast into a beach vacation destination. During this meeting, the Chinese government also invited El Salvador to participate in its Belt and Road Initiative, to which the Salvadoran government has made no formal commitment. Nor has the PRC recognized El Salvador as a “strategic partner,” as it has done with 10 other states in the region.

In addition to putting out the red carpet for President Bukele, insiders familiar with the matter note that the PRC also reportedly considers the president’s brother Karim an important figure in the relationship. The PRC and individual Chinese investors have also been active in courting Salvadoran mayors and local officials, who have become particularly vulnerable to such influence due to Covid-19’s detrimental effect on Salvadoran municipalities.

For its part, following El Salvador’s diplomatic flip, the United States not only signaled its concern over the advance of China in El Salvador, but began offering the country an expanded array of alternatives, including investing $1 billion to build a liquefied natural gas (LNG)-fired power plant in Acajutla through the Development Finance Corporation and launching the América Crece initiative to facilitate more such investments.

Adding to El Salvador’s sensitivity toward U.S. posture, the country receives 21 percent of its GDP in remittances (mostly from the United States), and Salvadoran immigrants in the United States are heavily impacted by decisions regarding programs such as Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and Deferred Action for Child Arrivals (DACA). The country is also strongly linked to the U.S. economy through the Central America-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) and stands to benefit from the $4 billion in U.S. aid the new Biden administration has promised for the Northern Triangle.

El Salvador’s experience with the PRC and its companies, as well as the United States’ reaction and ability to deliver on its own promises, will have a strong impact on the rest of the region as its governments contemplate their own orientation toward the PRC. (Currently, of the nine countries in the hemisphere that still recognize Taiwan, four are in Central America: Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Belize.)

The importance of such decisions goes far beyond questions of diplomacy. Recent examples, including Costa Rica’s recognition of the PRC in May 2007, Panama’s in June 2017, and the Dominican Republic’s in May 2018, illustrate that the new diplomatic posture brings with it a rapid advance in the PRC’s commercial position and influence in the economy, government, and society. In each instance, that advance has not only included a myriad of often nontransparent MOUs opening up the country’s market to Chinese companies and lucrative deals for politically well-connected business elites (some of whom travel to China with their government’s delegation), but also an increase in scholarships, student trips to China, and other forms of people-to-people diplomacy that shape the orientation and loyalties of these countries’ young professionals.

Trade

El Salvador’s trade profile with the PRC resembles that of many of its Central American and Caribbean counterparts which have changed relations to the PRC or are considering doing so. This includes a small domestic market open to purchasing Chinese goods and services; an export-oriented agricultural sector concentrated on coffee, sugar, and perishable fruits; and a lack of significant quantities of the petroleum, mining products, or soybeans that the PRC is interested in acquiring.

Like its counterparts, El Salvador’s trade with the PRC expanded significantly after China’s admission into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, although it has faced an ever-worsening trade deficit. The value of El Salvador’s exports to China rose from an almost insignificant $6.1 million in 2002 to $47.4 million in 2017, the year before it recognized the PRC. Over the same period, El Salvador’s imports from China have climbed steadily from $68.9 million in 2002 (over 11 times the value of its exports to China) to $920 million in 2017 (over 19 times the value of its exports).

The Sánchez Cerén government in El Salvador may have hoped that recognition of the PRC would facilitate more Salvadoran exports to China, but the opposite occurred. In 2018, the year El Salvador switched relations from Taiwan to the PRC, its exports to the country experienced a temporary jump to $85.5 million but then fell back to $51.9 million in 2019. On the other hand, El Salvador’s imports from the PRC almost doubled after forging diplomatic ties, from $920 million to $1.640 billion—but unlike its exports to the PRC, its imports continued to rise, reaching $1.723 billion in 2019. In other words, rather than create new opportunities for El Salvador, the principal effect of recognition on trade was to subject its market and producers to greater competition from China. By 2019, El Salvador was importing from the PRC more than 33 times the value of what it was exporting.

As happened in other comparable Central American countries, El Salvador’s deteriorating trade situation—despite recognizing the PRC—reflected multiple structural challenges.

With respect to tourism, the country’s high levels of gang violence and other sources of insecurity—and almost nonexistent China-oriented tourism infrastructure—impeded both visits by Chinese nationals and PRC investment in the tourism sector.

With respect to agricultural exports, El Salvador’s traditional products were simply not competitive against similar suppliers of undifferentiated goods in Asia, who did not have the expense of shipping their products halfway around the world (in refrigerated containers in the case of perishable fruit). El Salvador’s small size, which limited its production capacity, further decreased its appeal for PRC-based agricultural purchasers seeking to supply the vast Chinese market.

Nor did the Export and Investment Promotion Agency of El Salvador (PROESA) initially have the capacity to successfully market the country’s exports as high-end luxury products—as Chile did with its cherries, table grapes, and wines. PROESA’s director, Sigfrido Reyes, has played a key role in promoting economic ties with the PRC, but the organization itself continues to struggle to improve its outreach to the Chinese market and potential investors.

While individual Salvadoran businesspersons who participated in the early delegations to the PRC obtained lucrative contracts, El Salvador was simply not in a good position to take advantage of the expanding Chinese market. During Bukele’s December 2019 visit to Beijing, the Chinese government promised to import more sugar, coffee, and other specialized products from El Salvador. However, even if such an increase in imports were possible, the Covid-19 pandemic effectively froze the development of most new initiatives.

Logistics

In the early days of recognition, the PRC proposed a series of projects involving not only the construction and operation of port facilities, but also the establishment of six special economic zones (SEZs), which would cover 14 percent of the national territory, mostly in areas politically favoring Sánchez Cerén’s FMLN. The most significant proposed projects were focused on converting the port of La Unión into a regional logistics hub to be operated by Chinese companies. However, the initiative was blocked by a series of political, legal, and other obstacles, leaving its future uncertain.

Given that El Salvador already had a commercial port in Acajutla, the project in La Unión—which would have disproportionately benefited Sánchez Cerén’s supporters—bore an eerie similarity to the ill-fated Hambantota port project in Sri Lanka, where Chinese firms built a new port in a zone dominated by supporters of the ruling party despite an existing port in Colombo. Lacking enough trade to make use of two ports, in a dilemma with powerful lessons for El Salvador, the next Sri Lankan government was saddled with significant debt, ultimately leading it to lease the port and the land around it to China.

Importantly, the terms of the trade zones would have excluded companies already established in El Salvador (principally from the United States and Europe), allowing new Chinese companies—working in conjunction with Chinese port operators, Chinese shipping companies, and likely Chinese service providers—to dominate the zones. Moreover, due to La Unión’s location in the Gulf of Fonseca (at the intersection of Salvadoran, Honduran, and Nicaraguan territory) and El Salvador’s participation in a special customs arrangement with Guatemala and Honduras, the PRC would have been well positioned to expand its reach among El Salvador’s neighbors. It could have used La Unión and the associated SEZs to import Chinese products, employing Chinese companies to store these goods, carry out minor assembly and support activities, and distribute them to other Central American markets without involving local businesses. According to knowledgeable insiders interviewed anonymously for this work, Chinese investors are also interested in constructing an airport in La Unión, which would further bolster the zone as a multimodal hub.

Fortunately for those who would have been adversely impacted by competition from Chinese firms, the project has been stalled for the moment by multiple roadblocks. Japan, which had agreed to loan El Salvador $102 million to complete the port and had some legal leverage over its management, declined to cooperate. Indeed, on the way back from his state visit to China, Bukele met in Tokyo with then Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe, who reportedly warned Bukele of the perils of such Chinese projects. Moreover, as a political centrist, Bukele has not faced as much partisan pressure to commit Salvadoran funds to a questionable project that would have disproportionately advantaged FMLN-dominated zones.

Despite such difficulties, China’s development of La Unión and the surrounding area as a multimodal commercial hub remains on the table. The Japanese government is gradually extracting itself from management of the La Unión port, and insiders consulted for this work noted that there is talk in El Salvador of privatizing the port in 2022 and allowing a foreign (presumably Chinese) firm to manage it.

Behind the scenes, a Chinese-Salvadoran investor, Bo Yang, has begun purchasing territory that would be involved in the expansion of the port, including half of Perico Island. He offered residents of the island up to $7,000 each to relocate. While some initially refused, the purchase went forward at the end of 2019 and was registered in March 2020, though that registration has not yet been officially accepted yet by the Salvadoran government.

Other Physical Infrastructure Projects

As noted previously, the PRC made commitments to both the Sánchez Cerén and Bukele governments regarding a range of infrastructure projects to be financed and operated by Chinese companies. Although the Covid-19 pandemic paralyzed progress on almost all of them, they are now beginning to move forward.

The sports stadium, reportedly a priority for the Bukele government, is now in the preliminary phases of selecting a location and performing associated studies. Similarly, a site has not yet been selected for the new national library.

The water treatment facilities at Ilopango and La Libertad have both run into complications, leading the prospective Chinese builders to increase the price tag for Ilopango by $15 million and for La Libertad by $5 to $7 million, according to sources familiar with the discussions who were interviewed for this work. In particular, the water in Lake Ilopango reportedly has high levels of heavy metals and other contaminants, which will require incorporating special advanced filtration systems to avoid poisoning the population.

Of all the Chinese projects, the new tourist pier at La Libertad is the furthest along. Work only began on February 27 following the recent completion of a nearby highway bypass.

With respect to the “Surf City” project, Chinese companies have reportedly been offering to finance and invest in upgrades to a variety of hotels and other establishments in the proposed tourism zone, although they have not yet made progress on infrastructure specific to the $200 million initiative.

Beyond these activities, knowledgeable sources in El Salvador interviewed for this report that noted that Chinese investors have been quietly seeking to buy up land along the Salvadoran coast, including in La Libertad (particularly near the Acajutla port) and the department of Usulután (including islands in Jiquilisco Bay). These locations presumably present opportunities to build hotels and other establishments that will increase in property value once tourism activity in the area ramps up.

In contrast to other countries that have recently recognized the PRC, El Salvador has not yet seen Chinese companies play a significant role in road and bridge construction. However, China is reportedly interested in participating in the construction of a road near the Guatemala–El Salvador border in an area with significant coal deposits (although traditional mining is not currently permitted under Salvadoran law).

Telecommunications

As in other parts of Central America, the Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE have a major presence in the telecommunications market. Not only do they manufacture smartphones and other devices—for which Huawei has a dedicated customer service center in San Salvador—but they also supply goods and services to the country’s major commercial telecommunications providers, particularly to Movistar and Digicel (and, to a lesser degree, Tigo and Claro).

With respect to 5G, although Uruguay is the only country in the region to have implemented the new technology, El Salvador is close behind. Once Salvadoran telecommunications companies, in conjunction with the Salvadoran government, begin rolling out 5G networks, Huawei is positioned to be the major provider.

Intellectual Infrastructure

As with many countries in the region, the intellectual infrastructure in El Salvador for doing business with China is still relatively limited. There are a small number of politically well-connected Salvadoran businessmen involved in importing Chinese products, exporting coffee and other goods to China, and other commercial transactions. As noted previously, while the Salvadoran trade promotion organization PROESA has deepened its engagement with the PRC since recognition, it is still developing its capabilities.

As it has done in other countries following a change in diplomatic recognition, the PRC established a Confucius Institute in the country at the main, public University of El Salvador (UES). The latter began its official relationship with the PRC in December 2018, with formal planning for the institute beginning in May 2019 and the first Mandarin-language classes being offered that November. The school currently has four Chinese instructors focused on offering introductory Mandarin classes. Through the Confucius Institute at UES, China also sponsored 35 Salvadorans for university studies in China in 2019—which, given El Salvador’s small size, is significant relative to the number of students it sponsors in other countries in the region.

In the media space, the Salvadoran cable network TVX officially joined the Belt and Road media community on September 10, 2019. The network now transmits Chinese programming such as cultural documentaries, children’s programming, and Chinese soap operas. TVX director Julio Villagran is a frequent attendee at PRC-Latin America forums, and meets regularly with the Chinese ambassador to El Salvador, Ou Jianhong.

While there is a small community of Chinese Salvadorans, there is notably no “Chinatown” in the country. Moreover, few Chinese Salvadorans speak Mandarin, making it difficult to communicate with Chinese companies and tourists, and few have close connections to the PRC that could be of use in import-export or other businesses.

Covid-19 Diplomacy

In the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, the PRC and its companies donated limited quantities of personal protective gear, thermometers, and other medical supplies, as well as non-medical relief supplies such as shovels. China has not, however, provided more sophisticated equipment to El Salvador, such as ventilators or test kits, as they have done with other countries in the region. With respect to vaccines, El Salvador procured a shipment of the British AstraZeneca vaccine through India and has a contract in the works to acquire more vaccine doses from Pfizer. They have not, however, acquired any of the Sinovac, Sinopharm, or CanSino vaccines from China.

Security Engagement

In contrast to other countries that established diplomatic relations with the PRC, El Salvador has minimal security engagement with China. In 2020, according to sources interviewed for this work, a delegation from the People’s Liberation Army toured the Salvadoran military academy, and the PRC has reportedly discussed providing computers and other equipment to the Salvadoran National Civil Police. Chinese officials have reportedly offered other forms of security engagement but have consistently been politely turned down by their Salvadoran counterparts, and no known Salvadoran military personnel have attended professional military education courses in the PRC to date.

Conclusion

The example of El Salvador is instructive to Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, and Nicaragua, the remaining Central American countries considering changing diplomatic relations from Taiwan to the PRC. The China-El Salvador relationship arguably did more to expose local producers to competition from the Chinese than to expand export opportunities for Salvadorans. The PRC’s major proposed projects raised serious initial questions regarding transparency and who would reap the benefits, which would likely disproportionately accrue to elites within the FMLN, the political party then in power. Indeed, following the replacement of the FMLN government with Nayib Bukele and his Grand Alliance for National Unity, the application of principles of transparency and open competition is arguably what caused many of the Chinese projects to stall.

With the continued expansion of the Chinese market—and the associated growth of PRC-based companies and other institutions as sources of investment and finance—the PRC will continue to present opportunities to El Salvador. However, the current posture of the Bukele government raises hope that the country will strengthen its institutions and engage with the PRC within a framework of transparency, rule of law, and solid planning and analysis. There is a logical role for the United States as well—including through the Development Finance Corporation, América Crece, and the Biden administration’s promised $4 billion in assistance to the region—in helping El Salvador engage in a healthy way that protects the country’s long-term interests and sovereignty.

Evan Ellis is a Latin America research professor with the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute. The views expressed herein are strictly his own. The author would like to thank the U.S. Military Group El Salvador, among others, for their contributions to this work.

This report is made possible by general support to CSIS. No direct sponsorship contributed to this report.

This report is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2021 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.