Engagement With China Has Had a Multifaceted Impact on Latin American Democracy

While Beijing may not deliberately promote authoritarian regimes in Latin America, implicit risks to the dynamics of democracies arise out of engagement with China.

In its Global Civilization Initiative Beijing seeks to undermine the moral capital of the West on democracy and other values by positing the validity of other (unspecified) alternatives.

Beyond such discourse, China’s commercial and other engagement – and its increasingly dominant position in the technologies and systems that define communications and the new digital economy – has had a transformative effect on the dynamics of and discourse about both democracy and development globally.

As a result, China has had a complex and multifaceted impact on democracy in the Global South – including in Latin America, the focus of this article. This impact is simultaneously both deliberate and inadvertent, direct and indirect, and is principally felt through four channels: (1) the effect of engagement in undermining and altering the discourse about China in democratic societies as their members pursue benefits from working with China; (2) Beijing-sponsored training programs containing authoritarian narratives and content; (3) the impact of the Chinese “model” and associated technology architectures; and (4) the role of China as an incubator of authoritarian societies.

Undermining and Altering the Discourse About China in Pursuit of Benefits

As in other parts of the world, there is much interest in Latin America in doing business with China, including securing access to its markets and partnering with its companies and banks on local projects. This desire leads those interested parties to self-censor to avoid offending Beijing, and even engage in some self-serving China advocacy.

Topics known to offend China – and thus put potentially lucrative engagements with the country at risk – including referring to Taiwan as an autonomous or independent government, discussing repression in Tibet, speaking critically about China’s incarceration of millions of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, and discussing its takeover of and repression of democratic actors in Hong Kong and violation of its 1997 treaty commitments to the enclave, its militarization of islands and aggressive behavior toward neighbors in the South and East China seas, and its actions against Chinese dissidents. Negative comments about the risks of doing business with China and the record of individual Chinese companies with respect to their project performance, treatment of labor, subcontractors, and affected communities, as well as their environmental record and other aspects of corporate social responsibility, are also understood to be sensitive topics.

Beijing’s adverse reaction to such critical discourse is well-known in the region and globally, with China providing frequent reminders. These include sanctions against Australia after Canberra called for investigation of the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic; threats against the National Basketball Association when one of its players criticized China’s treatment of Tibet; and most recently, its suspension of a $5 billion portion of a credit swap with Argentina, following negative comments about China by the incoming government of President Javier Milei.

Beijing also recently suspended purchases of agricultural goods from Guatemala, sending a not-so-subtle message to the Arevalo administration that its ability to continue its modest agricultural exports to China was at risk if it did not switch its diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to Beijing.

When the Chilean government brought a well-founded anti-dumping action against Chinese steel companies, the head of Chile’s fruit growers’ federation, Fedefruita, spoke out publicly against the Chilean government’s action. The fear of Chilean fruit exporters that arguably prompted the remarks – that the action by their government could put their own (completely unrelated) access to the Chinese market at risk – illustrates how China’s reputation of being vengeful leads to selective suppression and distortion of the discourse about China in democratic societies.

Chinese Training Programs Containing Authoritarian Narratives and Content

China is increasingly active in Latin America and other parts of the world in conducting training programs in China for professionals from the region. Problematically, these trainings are rife with authoritarian content and narratives.

Beijing brings hundreds of Latin American journalists to the country each year for lucrative all-expense-paid visits in the name of training or conferences. These include China’s hosting of a delegation of 30 Honduran journalists as well as 25 from Nicaragua. Such trips not only engender the gratitude of the recipients of Chinese largess, influencing what they write about China, but arguably inculcate in them the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s authoritarian perspective on the role of journalists in relaying, rather than questioning, information provided by the government and other authorities.

China’s training for large numbers of military personnel, judges, and most recently, police from Latin America also arguably imparts lessons of an anti-democratic character, such as the CCP’s approach to crowd control and protesters, or its orientation for judges in deciding legal cases where the government is involved.

Scholar Niva Yau of the Atlantic Council recently concluded an important study reviewing thousands of Chinese language reports over international training programs. She found that the quantity of these programs – and the authoritarian narratives implicit in them – has increased substantially over recent decades. In the period from 1981 through 2009, the documents she examined showed an average of 142 programs per year with 4,285 persons traveling to China annually. During the later period, from 2013 to 2018, that number increased tenfold, to an average of 1,400 programs per year involving 40,000 personnel traveling to China.

Impact of the Chinese “Model” and Technical Solutions

By contrast to the Soviet Union, which advertised its communist “model” of governance and economic organization as an alternative to Western democracy during the Cold War, China has not overtly promoted its model as an alternative to the West. Rather, Beijing asserts that it is merely an example from which developing countries can draw lessons.

Nonetheless China has been increasingly aggressive in such indirect self-advocacy, including Xi Jinping’s speech to the 19th Communist Party Congress in which he offered “Chinese wisdom and a Chinese approach to solving the problems facing mankind.”

Apart from Beijing’s own assertion of itself as an example for others to follow, the world’s perception of China as making significant progress in economic growth, order, and efficiency arguably impacts debates about political and economic models, in ways far more effective than did the lackluster growth and heavy-handed authoritarianism of the Soviet Union. Even if such perceptions do not consider the actual limits of Chinese success, and its associated economic distortions, environmental, and human costs, they color contemporary thinking about the appropriate roles of the government versus individual initiative in economic development, and the role of command decision versus democratic choice, expression, and the protection of individual rights in the political domain.

In a similar fashion, the perceived results of Chinese technical solutions, including its interlinked security, financial, public services, and other architectures, arguably impact decisions in other countries about the degree to which individual privacy and protections should be ceded to achieve the potential gains in security and societal efficiency that new technologies, powered by artificial intelligence, promise to provide.

Beyond impacting future policy choices about technology architectures, as China-based entities increasingly lead the development and deployment of such architectures, decisions inherently privileging results over protection of privacy and the individual become the new reality. This path is further locked in as Chinese companies set the standards for those technologies and push others out of the competition.

China as an Incubator of Authoritarian Societies

Although Beijing engages with governments across the full ideological spectrum, its willingness to provide support to those moving in an authoritarian direction, without the political and other conditions that Western governments often place on such aid, impacts the political dynamics of Latin America as some of its governments move toward authoritarianism. China achieves such effects, in the course of pursuing its own commercial and other objectives, through providing both resources, and specific technology solutions to authoritarian partners.

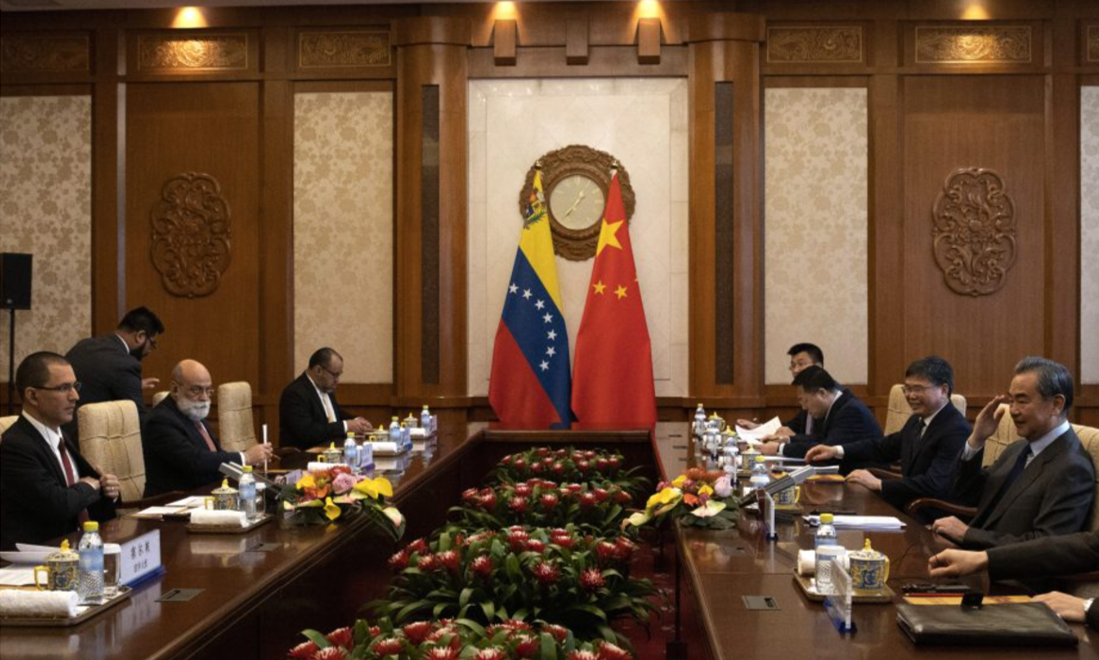

With respect to resources, the estimated $59.2 billion that China provided to the Chavez and Maduro dictatorships in Venezuela beginning in 2008, in exchange for oil, provided resources and opportunities for corruption that kept the Venezuelan regime afloat, while incentivizing regime cronies to remain loyal to its leadership.

In Nicaragua, the $567 million in commitments for work projects to be done by Chinese companies for the Sandinista government similarly provides the increasingly isolated authoritarian Ortega government with resources and associated opportunities for personal benefit.

With respect to technology, Chinese nationwide surveillance and control systems in Latin America include the ECU-911, sold to the populist authoritarian Rafael Correa regime in Ecuador; the BOL-110 system, sold to the Evo Morales regime in Bolivia; as well as the Fatherland Identity Card system, which is helping the authoritarian regime in Venezuela expand its social control.

In a similar fashion, China’s contributions to Cuba’s internet and telephone architectures were instrumental in allowing that dictatorship to cut protesters off from each other, and from the outside world, and thus to maintain control during the unexpected Cuban national uprising of July 2021.

Recommendations and Conclusions

While there is little evidence to suggest that China deliberately promotes authoritarian governments over Western style democracies in Latin America or elsewhere, governments of the region must recognize the implicit risks to the dynamics of democracies (already under considerable stress) that arise out of their commercial, political, and technological engagement with China. The risk factors include the “soft power” of expected benefits, the corrupting and authoritarianism-promoting effect of training junkets to China, plus the increasing adoption of technology solutions from China-based companies.

The appropriate way for Latin America and other parts of the world to safeguard democracy is not to forgo profitable commercial and political interactions with China. Rather, it is to ensure that such interactions are conducted within a framework of utmost transparency, a level legal playing field, and strong institutions that include adequate capacity to review contracts, proposed acquisitions, and other deals involving Beijing.

Governments must also do more to recognize the inherent conflicts of interests when their officials (including at the local level) receive lucrative all-expenses-paid trips to China. While democratic governments cannot easily restrict private citizens such as journalists or academics from making compromising trips to China, transparency about such benefits, including business opportunities with China accruing to ambassadors and other senior officials after their time in service, should receive greater attention in interpreting the pro-China discourse of such figures.

The United States, like other governments, has a stake in the continued health of democracy in Latin America, and has a strong interest in doing more to provide alternatives from investment projects to training programs. Nonetheless, whether or not Washington does better by Latin America, it will not absolve the region and its leaders from their duty to protect their countries’ democratic institutions, and freedom of expression and action.

This article is based on an address given on June 25, 2024, to the distinguished Argentine think tank Fundación Libertad,