Would Venezuela Really Invade Essequibo?

In the context of unfolding global conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine and the dangers of an increasingly aggressive yet economically fragile People’s Republic of China (PRC), Venezuela’s provocative referendum on its claim to two thirds of the territory of neighboring Guyana has received understandably little attention in Washington, D.C.

In seeking legal action from the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the government of Guyana presented evidence not only that Venezuela was holding a referendum on a decision not yet resolved by the Court but that it was seeking to use the preordained results of such a vote to justify military action in the Essequibo following the vote, calling attention to Venezuela’s construction of an airfield near the border which could be used to support an invasion, and its conduct of military exercises in the area

This work examines motivations behind Guyana and Venezuela’s current actions on Essequibo, considerations for possible future actions, and the implications for the U.S. and the region.

Background

Venezuela’s claim to the Essequibo region, under Guyanese legal control since an international arbitration tribunal ruled on the border between the two countries in 1899, is based on the argument that the ruling in Guyana’s favor was invalidated by improper collusion between the British and Russian judges who, together with two American judges, decided the case. The collusion claim has some substantiation in a memoir made public after the judges’ death but does not necessarily invalidate the longstanding 1899 decision.

In the Geneva Agreement of 1966, the parties agreed to seek a negotiated settlement of the land boundary issue and only pursue a remedy in the courts if negotiation failed. The question of Venezuelan versus Guyanese jurisdiction in the Caribbean waters to the north of both countries, where over 11 billion barrels of recoverable oil have been found, is only partially addressed by the legal dispute over the land border.

In 2018, in the context of incidents in 2013 and 2018—in which the Venezuelan military intercepted oil exploration vessels in the disputed region—operating with the authorization of Guyanese government, and the 2015 Venezuelan declaration of an “Integral Defense Zone” (ZODI) covering the region (and parts of Colombian waters), United Nations Secretary General Anthony Gutierrez found that attempts at negotiated settlement had indeed failed, and per the terms of the Geneva agreement, referred the matter to the ICJ. ICJ consideration of the case was delayed first by the COVID-19 pandemic and then by a Venezuelan challenge to its jurisdiction, which the Court dismissed in April, 2023. Such dismission positioned the court to now decide the case on its merits, with both parties having previously accepted compulsory ICJ jurisdiction, and not having subsequently withdrawn it via the legally proscribed means for doing so.

The Question of Venezuelan Intentions

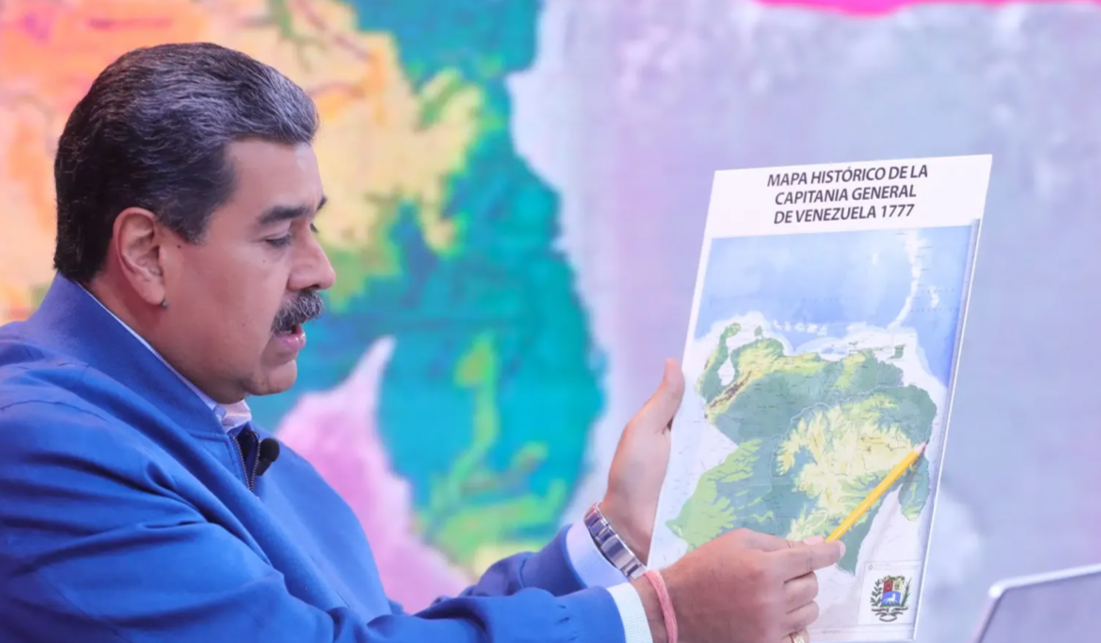

While the motivations of the Maduro regime in holding the referendum on Essequibo on December 3 are likely only known to Maduro and his inner circle, they probably reflect a combination of domestic political maneuvering and the creation of international options if the ICJ rules against Venezuela.

Internally, the Venezuelan claim to Essequibo is one of the few issues on which the Maduro regime and the opposition agree. The current Maduro referendum may be part of a multi-pronged strategy to undercut the opposition in the potential 2024 Presidential elections.

On the international front, Maduro may be seeking to transform the legal issue into an ideological one, pitting the U.S. from which Guyana would most likely seek protection if Venezuela invaded Essequibo, against an “anti-imperialist” and anti-U.S. “interventionism” coalition of Maduro and sympathetic leftist governments in the region, including Gustavo Petro in Colombia, Luís Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil, Nicaragua, Cuba, Honduras, and possibly Mexico.” Maduro’s November 2023 false claim that the U.S. sought a military base in Essequibo illustrates such tactics.

In light of Venezuela’s continued economic problems, Maduro may also be seeking to take advantage of the new regional political correlation of forces in his favor to extort the Exxon-led coalition of international oil companies to provide payments or services and other benefits to Venezuela. In return, Maduro could refrain the Chavista government from military and other harassment of the commercial exploitation of Guyana’s offshore petroleum reserves. Chevron’s October 2023 buyout of the 35 percent Hess stake in the Exxon-led coalition for USD 53 billion could theoretically change the consortium’s vulnerability to such extortion and the value it could provide to Venezuela, given that Chevron is the key remaining Western partner in Venezuela’s oil blocks, operating in conjunction with the Russians.

The more complex yet vitally important related question is whether, as suggested by the content of Guyana’s petition to the ICJ to stop the referendum, the Maduro regime has plans for military action in Essequibo or is willing to risk the escalation of the conflict into military action meaningfully. Because Essequibo, representing 2/3 of Guyana’s territory, borders Guyana’s capital itself, Venezuelan aggression would profoundly risk the political as well as economic viability of the country and re-open the Pandora’s Box of inter-state warfare in the Western Hemisphere.

Although Venezuela’s military is vastly superior to the Guyana Defense Force (GDF) in numbers and equipment, Venezuela would likely have significant problems moving forces into and sustaining combat operations in the vast Essequibo region, mainly if the GDF and its reserve, with support from the U.S. and others, mounted an effective resistance against them, as Ukraine did against Russia. Indeed, by contrast to Russia in the Ukraine, a failed military campaign in Essequibo could arguably break the Venezuelan military and turn it against the Maduro administration in ways that sanctions and other pressures on the regime could not.

Suppose Maduro is indeed willing to take military action in Essequibo. In that case, he is likely emboldened by his successes in convincing the Biden administration to suspend for six months a broad array of sanctions against the regime, permitting it to receive up to USD 1.4 billion in additional oil revenues. This would dramatically strengthen the regime and its ability to mount military adventures such as Essequibo without having to make concessions that would have put regime continuity at risk, such as a free and fair election against Maria Corina Machado, the candidate that the opposition rallied around through an overwhelming vote backed by unexpectedly high participation.

Maduro may further be gambling that the U.S., is bogged down in simultaneously supporting allies in significant wars in Ukraine and the Middle East while trying to hold the PRC at bay over Taiwan. Additionally, the need of Venezuelan oil to insulate against skyrocketing petroleum prices partially, results in the Biden Admiinistration´s potential willingness to overlook future regime bad behavior, just as it appears to be reneging on electoral commitments made to secure sanctions relief.

For Maduro, the appropriation of Guyana’s offshore oil wealth, if he could convince the oil companies to continue production under Venezuelan control or expropriate their assets without losing most production, would substantially increase Venezuela’s diminished production capacity, bringing his regime a windfall, particularly with elevated oil prices due to the expanding Middle East conflict.

Conclusion

Although the Maduro regime’s moves to appropriate Guyana’s Essequibo region are likely mere political posturing, gamesmanship, and attempts at extortion, the U.S. should act prudently, if discretely, to contain the risk. Public U.S. moves to defend Guyana against Venezuelan aggression would feed Maduro’s desired narrative about Yanqui imperialists, allied with “big oil,” against the sovereignty of the region. Instead, the U.S. should quietly work with the Ali government in Guyana to prepare for the low but real risk of Venezuelan military aggression while telegraphing through private messaging and observable Force movements the United States’ intention to commit itself to Guyana’s defense if Venezuela attacks it. The Biden administration should also make it clear that the U.S. will impose the strongest possible sanctions against petroleum or other companies operating in Venezuela or territory occupied by the Venezuelan regime.

Consistent with the recommendations of the well-thought-out November 13, 2023 letter to President Biden by Senate Foreign Relations Committee Ranking Member James Risch and other concerned Congresspersons, the Biden administration should move away from its counter-productive attempts to advance democracy in Venezuela through lifting sanctions. The policy has not only been ineffective but has arguably strengthened Maduro’s hand economically and politically, emboldening him both to consolidate his authoritarianism domestically and to threaten neighbors such as Guyana.

As in the response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. and the world should not dismiss illogical, counter-productive aggression as impossible. Deterrence against a low-probability threat is inconvenient but always cheaper than responding to aggression once it has begun.