Leveraging Latin America's Embrace of the United States

In recent months, the assertive policy of the Trump administration toward Latin America, from Panama to Mexico to Venezuela to Colombia, has received significant media attention. Ironically, for reasons largely unrelated to that engagement, a confluence of political currents in the region is giving rise to a group of governments, almost unprecedented in number, aligned with and interested in strengthening relations with the United States. That trend presents the new U.S. administration with enormous strategic opportunities as it gives increased attention to the region in its foreign and domestic policies, as key to U.S. security and prosperity. That fleeting opportunity could evaporate, however, if its causes and complexity are not properly understood, and the tentative goodwill in the region is not aggressively leveraged through U.S. outreach based on respect, democratic values, rule of law, and mutual support.

The common driver in Latin America’s widespread—though varied—shift toward U.S.-friendly governments is bad experiences with past left-leaning regimes and apprehension about new ones, rather than a direct response to current U.S. foreign policy.

- Argentina: The November 2023 election of the pro-U.S. libertarian government of Javier Milei was driven by voters’ disillusionment with the corruption and economically disastrous clientelist policies of previous Peronist leaders, including Cristina Fernández and Alberto Fernández.

- Bolivia: The disillusionment with corruption and deepening economic and political crisis under the leadership of indigenous cocalero leader Evo Morales and his successor, Luis Arce, paved the way for the October 2025 election of Rodrigo Paz Pereira, whose first actions included seeking to reestablish relations with the United States.

- Chile: The selection of a communist, Jeannette Jara, to represent the leftist Concertación coalition has strengthened the odds of a victory by the ultra-conservative candidate José Antonio Kast in Chile’s November 2025 elections.

- Colombia: The explosion of criminal insecurity, illegal mining, cocaine production, and associated corruption that has come from the failed security policies of Gustavo Petro creates a substantial likelihood of a return to the right in that nation’s May 2026 national elections.

- Ecuador: The April 2025 election of Daniel Noboa was enabled, in part, by fear of the return of the left authoritarian populism of Rafael Correa through his perceived surrogate, Luisa González.

- Guyana: The September 2025 reelection of the People’s Progressive Party government of Irfan Ali continues the country’s orientation to work with the United States on security, oil, and other matters, even as it also engages economically with the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

- Paraguay: President Santiago Peña and his conservative, long-ruling Colorado party have historically been leery of the communist PRC, and have continued a policy aligning the country with Taiwan and the United States.

- Peru: Concern with the leftist course pursued by former President Pedro Castillo and his more ideological, Cuba-trained mentor, Vladimir Cerrón, led his successor, Dina Boluarte, to strengthen relations with the United States, a posture continued by José Jerí, who replaced her following her ouster by Congress in October 2025.

- Suriname: The National Democratic Party government of Jennifer Geerlings Simmons, elected in July 2025, has maintained a cooperative stance toward Washington.

- Uruguay: The center-left Broad Front government of Yamandú Orsi in Uruguay has taken a pragmatic but generally U.S.-friendly approach.

- Venezuela: For the first time in over 25 years, U.S. military pressure on the Cártel de los Soles has made the prospect of transition to a more S.-friendly regime appear realistic.

The general shift in Latin America toward aligning with the United States has left only Brazil, under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, as a major—if somewhat lukewarm—opponent of the United States in the region and collaborator with extra-hemispheric U.S. rivals including Russia, Iran, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

Central America, except for the leftist Libre government of Xiomara Castro in Honduras and the authoritarian dictatorship of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo, is also leaning toward being more U.S.-friendly. That pro-U.S. orientation spans a range of ideologies and government styles, from the left-of-center government of Bernardo Arévalo in Guatemala, to the more right-leaning Rodrigo Chaves Robles government in Costa Rica, to José Raúl Mulino in Panama, to John Antonio Briceño in Belize. Belize even helps the United States through its continued support for Taiwan and agreed with the United States in October 2025 to host migrants seeking asylum in the United States.

The Central American trend of embracing ties with the United States also includes the populist government of Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, who is closely aligned with U.S. President Donald Trump’s actions against transnational gangs. In Honduras’ national elections on November 30, currently too close to call, two of the three candidates, National Party candidate Nasry Asfura and Liberal Party candidate Salvador Nasralla, both advocate closer relations with the United States, as well as switching diplomatic relations from the PRC back to Taiwan, with which Honduras had relations until March 2023.

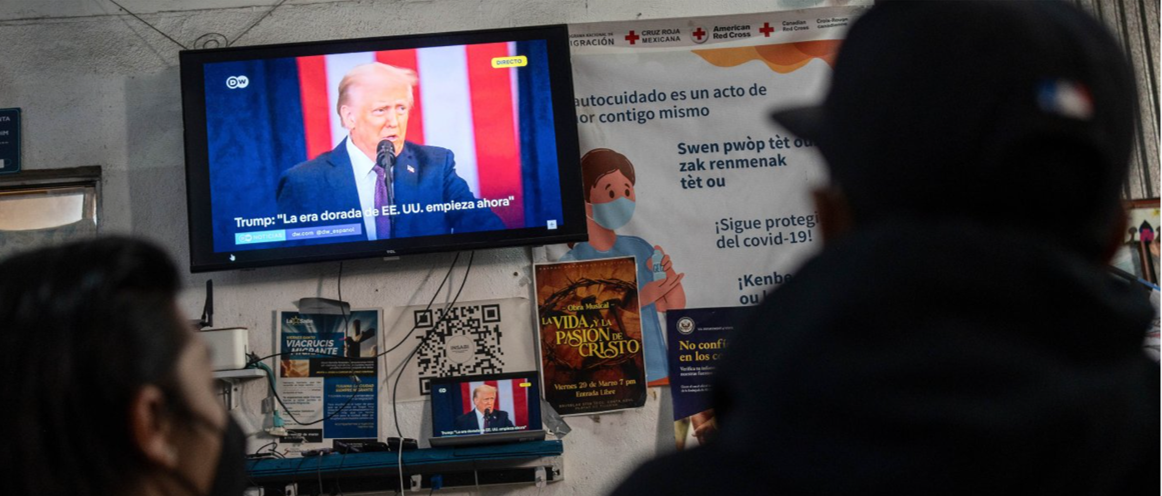

In Mexico, despite the leftist populist orientation of the ruling Morena party, and the deeply left ideological orientation of President Claudia Sheinbaum, the country’s strong dependence on the United States for exports, supply chains and investments, and the current review of the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) upon which the Mexican economy largely depends, has led President Sheinbaum to adopt positions on trade, security and other matters generally cooperative with and deferential to the U.S. government.

In the Caribbean, whose governments have historically been skeptical of, yet cooperative with the United States, Washington has strengthened its position through close relationships with the government of Luis Abinader in the Dominican Republic and Kamla Persad-Bissessar in Trinidad and Tobago, who has strongly supported U.S. actions against Venezuela’s Cártel de los Soles, among others.

The impressively widespread U.S.-friendly disposition of the region, arguably even greater than during the first Trump administration, creates substantial strategic opportunities for the United States in regional multilateral bodies, as well as in economic, security, and other domains, yet with caveats and limitations that must be understood and carefully navigated.

In recent months, U.S. threats of military action, tariffs and sanctions, and other measures against countries of the region have generally led them to cooperate with and temper their criticisms of Washington. That has particularly been the case for smaller states in Central America and the Caribbean, and those more economically tied to the United States, such as Mexico. As illustrated by the preceding paragraphs, however, receptivity to the United States has benefited greatly from the massive political shift in the region, a phenomenon largely unrelated to the new U.S. policies and tone, and arguably despite them. There is no guarantee, however, that this fortuitous coincidence of political conditions will persist, and reasons to worry that it may not.

Historically, when right-oriented governing coalitions have failed to adequately address insecurity, corruption, and the economic needs of their populations, the momentum has shifted back to the left. The failure of the wave of pro-market, U.S.-friendly governments that came to power in Latin America in the 1990s to address the needs and expectations of their populations led to the “pink tide” of leftist regimes across the region in the early 2000s.

Given the importance of delivering results, U.S. initiatives such as the bank swap and loans to stabilize Argentina’s economy, security support to Ecuador, and the encouragement of U.S. technology investment in Paraguay and the purchases of its beef are strategically wise. Still, there are reasons to doubt that such support will be sufficient to allow Ecuador to overcome its crisis of public insecurity, or allow the Javier Milei government in Argentina to weather continued runs on the peso. The United States’ current deep cuts in developmental assistance and democracy programs, however valid or not the reasons, further decrease important sources of U.S. leverage to help its friends succeed.

The advance of China in the region, and the often-corrupting leverage of its expanding economic engagement, is another factor only partly addressed by the region’s U.S.-friendliness. U.S.-oriented governments in the region often partly accommodate concerns about the PRC, including Taiwan-recognizing states such as Paraguay, Guatemala, and Belize, which persist in that posture despite being wooed and pressured by Beijing, not conducting significant military or other security engagement, and for some, like Costa Rica, limiting PRC presence in sensitive sectors such as telecommunications and space. Still, most are unwilling to reject export opportunities to, or loans and investment from, the PRC, despite the influence that comes from those expanding economic entanglements and the people-to-people relationships that come with it.

The U.S. government currently has a historically unprecedented level of Latin America knowledge among senior Department of State leaders, complementing its increased attention to the region. Leveraging the historic opportunity provided by the region’s current U.S.-friendly political configuration, however, requires a coherent approach, simultaneously strengthening collaboration on security, commerce, development, and institution-building, leveraging shared commitments to democracy and rule of law, people-to-people connections, and regional multilateral institutions. A principally transactional, ad hoc approach and a disposition to rely on economic and military coercion more than offering value and benefit will ultimately be counterproductive, particularly at a moment in which the PRC stands poised to exploit dissatisfaction with the U.S. approach. At the same time, however, returning to previously failed approaches built around imposing a partisan social agenda and a particular concept of democracy and rights would be equally misguided. If excessive reliance on coercion ultimately backfires, focusing on politically correct activities not optimized to U.S. partners’ orientations and needs is equally destined to fail.

For the United States not to squander the current bounty of U.S. receptive regimes in the region most directly connected to its security and prosperity, it should embrace an expanded, yet pragmatic and bipartisan partnership. This partnership is built around the concept that investing in a secure, prosperous region with strong and democratic institutions is fundamental to inoculating the region against criminals, terrorists, populist authoritarians, and extra-regional adversaries. In short, investing in the Western Hemisphere in a fashion that goes beyond improvisation and transactionalism is fundamental to putting “America First.”

Evan Ellis is a senior associate (non-resident) with the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. The views expressed in this work are strictly his own.